- Studio Dirt

- Posts

- Our Funeral

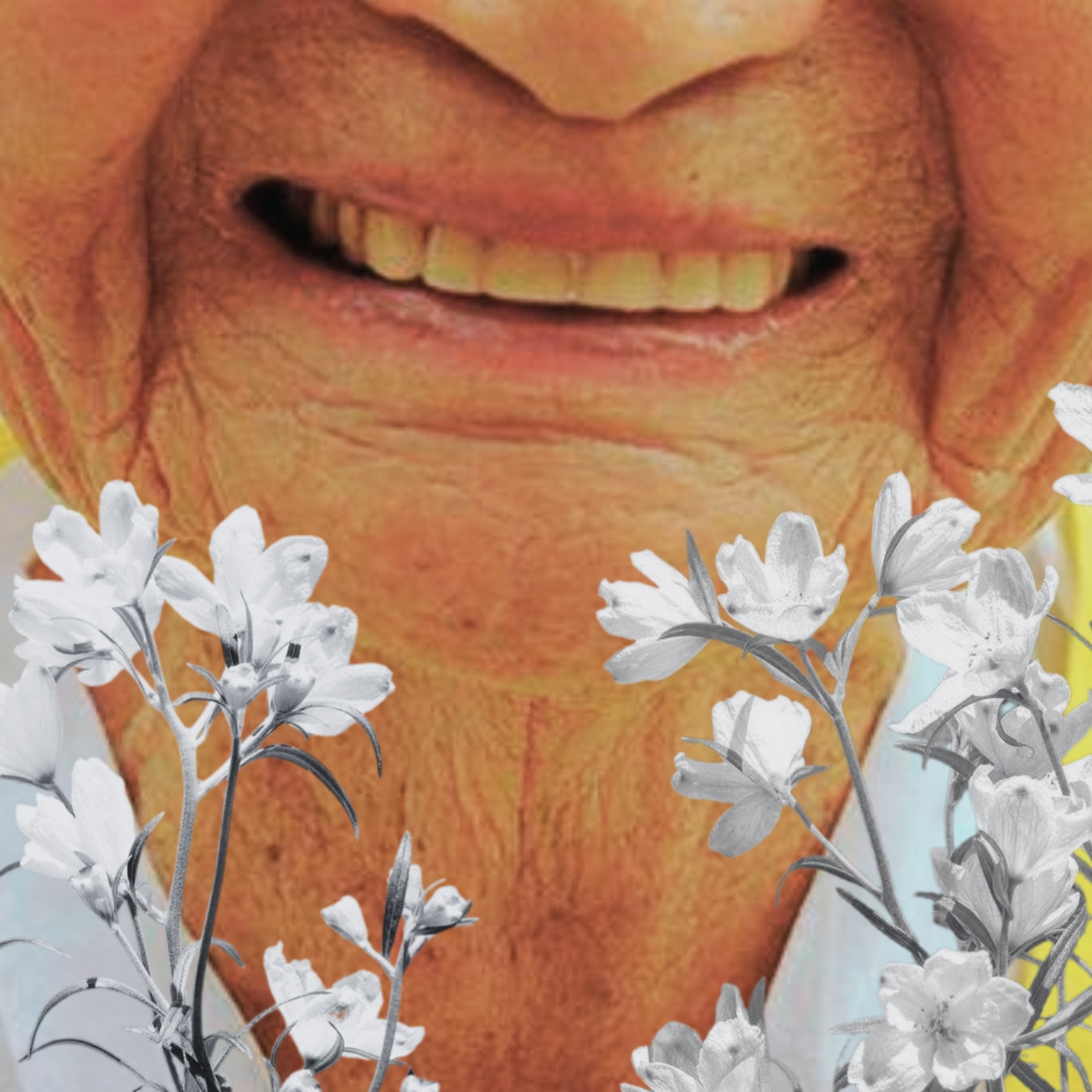

Our Funeral

"I am his descendant and of course it isn’t easy to be a descendant."

This is the first story of our fifth fiction week.

Stephanie Wambugu lives in New York City. She was born in Mombasa, Kenya and grew up in New England. Her debut novel Lonely Crowds will be published by Little, Brown in 2025.

It is late when I land in Nairobi. There is a long line for Americans in need of visas for entry. And I am in the line with the other Americans since I am an American.

Outside, visa in hand, I stand and wait for my cousin who is supposed to pick me up, but who has not been responding on WhatsApp. Though it’s December, it is 90° because I am in a city on the equator. And even though I have not been to this city in many years, the city I am from, it all strikes me as familiar, and if I don’t speak, if no one hears my accent, I might even pass as a local. To dirty looks, I begin to smoke a cigarette, and I don’t know if it’s because I’m smoking so near a family with children or because it isn’t very acceptable for a young woman to smoke here. I’m sure that if my mother or father saw me smoking they would be disappointed, but I haven’t seen my parents in several years and it is unlikely that I could disappoint them anymore than I already have. They called me last week to let me know that my grandfather had died and volunteered to pay for my airfare to come and mourn him. It would be unseemly for me to be absent from the funeral when all the other cousins would be there, they said. Finally, I see my cousin David and we recognize one another from our profile photos on Facebook. Recentish pictures that portray us as the adults we are now. David is pictured in his profile with his white wife. An English woman who lives in Kenya and works as an interior designer. I’m pictured alone on Facebook. I have no husband, no wife, no children, not even a dog. I’ve made my presence on the internet as non-descript as possible, so as not to betray anything about my personal life to my relatives, who I’m certain look me up from time to time for signs of life. David lifts my luggage into the back of his sedan.

I’ve made my presence on the internet as non-descript as possible, so as not to betray anything about my personal life to my relatives, who I’m certain look me up from time to time for signs of life.

On the dark highway, we are stopped by police. Four skinny officers with rifles in green uniforms. We’re asked for a sizable bribe. I complain, but David tells me to be quiet. He pays the bribe. When I tell David that it’s a shame that corruption is so prevalent here, he laughs. David tells me I’m like his white wife, that I think of everything in terms of justice. That’s why I don’t speak to my parents and that’s why I could never live in this country because I think only in terms of fairness and like all Americans I’m naive. Because David is a kind and gentle man, these judgments don’t register as insults at all, but as facts shared by an impartial witness, though a member of one’s family is never impartial and David is a member of my family.

We arrive at our uncle’s house where everyone is gathered for a meal to memorialize our family’s patriarch. I'm greeted by relatives I haven’t seen in years. It’s odd to be surrounded by so many people who share my features, who share common ancestors and come from the tribe I come from. I say hello to my other cousins, forgetting some of their names. My grandfather was a polygamist with dozens of children, forty-two sons and daughters as far as we know, but likely more. He is responsible for this large family cast across the globe. Some of us live in American cities, such as New York or Los Angeles or Atlanta. Another lives in South Korea with many biracial children fluent in Korean, Swahili and English. There are those in London, and others still in Lisbon. It’s a joke between us all that wherever you go in the world, you’ll find one of us there. Like an empire, we always say.

I don’t know if my parents are at the party or have already left or have not yet arrived. It’s a large property and easy to miss someone in the crowd. It’s possible they’re avoiding me. I’m staying in a hotel a few miles away from here. Could it be that they are staying in the same hotel? I sit alone in a corner of the large yard and my uncle approaches me. He is a very tall man and very commanding. He does not look at you as he speaks to you, to create, I think, the impression that you are not important. Still he is beloved, and respected as the eldest son of forty plus children. And it’s his home and when he approaches me, I stand up and open my arms to embrace him, but he does not embrace me. “Your voice disgusts me,” he says, “When I hear your voice I feel sick. Stupid, arrogant American. That’s what I hear. I suppose you’re proud,” he says, “That you hurt your mother and father. And wrote terrible things about them. The lives of children who dishonor their parents always end in ruin,” he says, “and you’re no different. You’re disgusting,” he says.

For a moment, I wonder if he was sent to say these things to me? Were these the sort of things my parents said about me? He sees someone he knows, a more important guest than me, and he calms down and turns to them and is gone. And in a way I’m relieved because it’s true that I often walk down the streets of the city where I live anticipating a similar confrontation. I imagine most people walk down the streets they live in expecting to be met with similar reproaches: someone who will remind them that they are stupid, arrogant, disgusting and doomed. And once you hear these things, said explicitly, as we all will one day, you feel nothing short of total relief because you don’t have to walk around in anticipation anymore of what you already know.

Alone, I have another drink and without saying goodbye I stumble out of the property, past the armed guard, with my luggage in tow and I call a taxi. When the taxi comes it takes me to my hotel and when I am in my hotel, in the bar in the lobby, I drink three more cocktails. Once I am very drunk, I turn to the man in a suit drinking alone at the end of the bar, a businessman I’m sure, a married man, a lonely man. I invite him up to my room. He is older than I am and he is winded from the short walk up the stairs. It’s a large, clean room. It’s more than I would typically be able to afford, but since my parents paid for my flight, I am able to pay for it easily. The room has a large bed made up in ironed white sheets. Spread across the bed with my clothes off, I call this man over. He struggles with his shirt buttons, then struggles with his belt. He has had more to drink than I have had. Naked and soft, he tells me that he can’t get an erection. “I can’t get hard,” he says. I tell him it is understandable but that he should probably go. I am tired and I didn’t invite him up for anything but sex, so there is no use in him staying. He agrees, sex is all he wants, too. Then I’m alone and I wonder again if my parents have chosen the same hotel. I wonder if they are on my floor. I wonder if they have seen me without me seeing them.

Once I am very drunk, I turn to the man in a suit drinking alone at the end of the bar, a businessman I’m sure, a married man, a lonely man.

I chose the hotel because it is advertised as having quiet rooms with desks, good for traveling businessmen. I came on this trip intending to write, intending to mine the situation for material. Anything remotely interesting that happens to me, however private, devastating or exposing to me or to others, I put in my writing. That is why my parents won’t speak to me because I used and continue to use them in my writing and they aren’t happy about that. Why do you have to write about abuse, and alcohol, and theft and depravity and sacrilege and terrible men and women and awful childhoods and all these sordid things? You had a good life, they say, and yet you make yourself out to be this really downtrodden, sick, beleaguered person. Why? It isn’t true. It hurts them to be the parent of such a shameless person, when they themselves have so much shame. So much so that they won’t speak to me. But now my grandfather is dead, so exceptional circumstances have made them extend this generosity to me. Death is an exceptional circumstance.

In the morning, I wake up nude, drool hard and dry on my face. I waste the day drinking. I scribble a few sentences on the back of a napkin but when I read them back I discover they’re garbage, unusable. My ability to fuck off an entire day is really unparalleled. At night, I end up at a nightclub full of tourists. I fall into this crowd of girls and guys from London and I wind up in a trio with two of them. The man is friendly, but square and when he tells me that he is a banker it makes perfect sense. The woman with him comes on to me and buys me many drinks. I am drinking vodka, neat and have been on the precipice of blacking out for hours by the time we leave for the banker’s rented bungalow.

The three of us begin to undress, intuitively, without saying anything. The woman, red haired, is the first to break the silence. She explains that she would like to do anal and the man is happy to oblige, but has to look for the lube. The way he says, “Sure, but I have to look for the lube,” so off-handedly makes me understand that they have been here before, at this exact impasse before and that I am the newcomer, meant to bring some excitement into the monotony of their relationship. I chime in to say that I’ll just take it regularly, meaning vaginally and they nod enthusiastically so as to say, that’s totally fine. Rifling through his nightstand, the man finds a bit of molly and I take some. He also finds a jar of coconut oil and I take some of that and put it between my legs. He offers the oil to the woman, but she says she’s sensitive to certain oils and would really prefer they use the lube.

The sun is coming up by the time we begin to make out and touch one another in the wide bed.

It is a whole ordeal searching for the lube. I’m quite high and bored. I also wonder how I look in this equatorial city, the only Kenyan with these white tourists on holiday, doing the same things I do in New York. Basically squandering my life. The sun is coming up by the time we begin to make out and touch one another in the wide bed. The man can’t get hard. I’m disappointed that this keeps happening and while the woman in bed is toying with him, trying to get him excited, I take my clothes and slip out of the house without saying goodbye. I walk toward the main road, trying not to call attention to myself. I cut through a busy open air market trying not to meet the eyes of passing women. There's a bit of oil dripping out of my crotch and running down my leg, just as there are tears falling from my chin. I touch my face and see that it is wet and I wonder if it’s from the drugs or if it’s some old sadness for my dead grandfather. I am his descendant and of course it isn’t easy to be a descendant. Just as it isn’t easy to get hard after a long night of drinking. Sometimes threesomes fail, just as the hopes you have for yourself often fail. Moving through the crowd of women in veils and girls in mini skirts and small children cleaved to their fathers, I tell myself it is alright, that one day all of this bad sex I am having will make me wise. One day I’ll have descendants, also.

From a distance, I see a familiar figure, wearing a long, patterned dress, fanning her face in the heat. I write it off. The woman comes closer, a man trails behind her, walking with a cane. Then I know with total certainty. There’s my mother and there’s my father. They are older than I remember. And I am also older.

I am face to face with them. We obstruct the sidewalk. People move around us.

“You look awful,” my mother says, “But I’m glad to see you.”

“Yes,” my father says, “awful, just awful, but we’re glad to see you, all the same.”

READ MORE FICTION FROM DIRT

|

|

|

|