- Studio Dirt

- Posts

- A room of string

A room of string

Worrying with Alexandra Tanner.

Becky Miller and Alexandra Tanner discuss Tanner's debut novel, Worry.

“‘Is this Deadliest Catch?’ ‘Na, but it’s kind of like it.’” It might not be the Bering Sea, but the stakes are life and death in Worry, the anxious, Internet-chatter-infused debut novel from Alexandra Tanner. When life on the couch in Brooklyn becomes as choppy as Alaskan crab fishing, sisters Jules and Poppy unravel.

The novel oscillates between venomous screaming matches and the quiet, dark register of late nights “getting stoned and fretting about the future.” The sisters, fighting for their survival in a modern maze of technological and moral extremes, are pitted against each other. Like a politically correct fly buzzing in your ear, Poppy attempts to find morality and fulfillment in New York; Jules, the narrator, drags us through toils of emptiness and misery, unable to stop staring at Mormon mommy bloggers long enough to think through a real thought. With their three-legged dog, Amy Klobuchar, Jules and Poppy attempt to form a family out of fracture, but splinter from each other and themselves.

Despite being bad sisters, bad Jews, bad daughters, and bad New Yorkers, Jules and Poppy try to build “a room of string” out of the scraps they find left in the 21st century. This undertaking goes beyond the pages of the book. I spoke to Alexandra Tanner about being online, crazy moms, vacationing, and cultural religion.

Becky Miller: What are some literary influences that imprinted on this book?

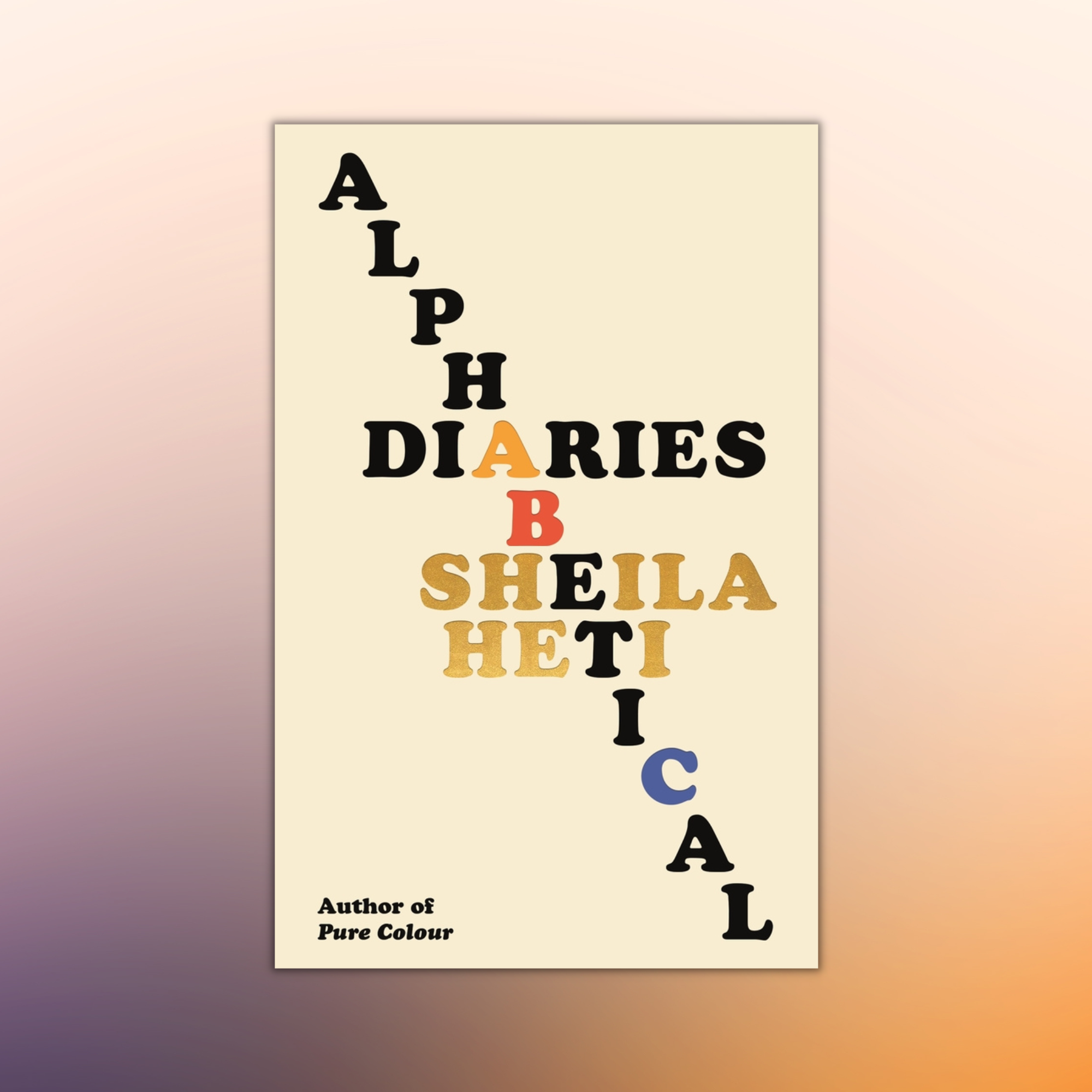

Alexandra Tanner: I have a lot, because I feel like the book pulls in so much of my own reading and my own investigations on the internet. Sheila Heti has been huge for me for a long time. I feel like there was a before and an after for me reading her, and being like, “Oh, there’s everything else, and then there’s the truth that comes from doing something like this.” That was a big one for me. Joy Williams is another one. She’s a really dense, nihilistic, opaque writer’s writer. Gabrielle Lutz is another one who’s just writing these really mordant, emotionally horrible, short glimpses of life that I was like, “I want to capture that.”

BM: Where did you get the names Jules and Poppy from?

AT: Poppy came to me right away. It felt so funny to me that Poppy is not the girl you picture when you picture a girl named Poppy. It was just right there, and it was a punchline of its own to me. And then, Jules, she didn’t have a name for a long time, but I didn’t want that to distract from the book. It started to feel like it was becoming a device. I agonized for a few weeks over what to give her. It couldn’t feel arbitrary, but Poppy is a hard name to compete with. It has to take the back seat. Jules sounded cool to me and with Jules and Poppy in contrast with one another, it felt like they were pulling different weights.

BM: When Jules and Poppy leave their apartment and go on vacation, their tensions seem to either ease or inflate. How do you think that vacations function in Worry?

AT: Vacation is terrible. I remember when I was growing up, my sibling and I would be on these family vacations to beautiful places doing beautiful things, and we would be miserable and we would be at each other’s throats the whole time. You’re out of your environment, and there’s this pressure to enjoy and push aside real life, and you can’t because you’re there, you’re inside of yourself. With both departures from Brooklyn, I wanted them to have that pressure to be having a good time or to see it as an opportunity to break a set of patterns, but that’s not how it functions. You’re going to be miserable on vacation. With the drudgery of work, vacation is the one relief we have, and it just can never measure up.

BM: There’s an SNL skit where Adam Sandler is playing this guy who runs an Italian travel company, and the whole commercial is, “You’ll still be yourself in Italy.”

AT: Oh my god, I know that one. The first time I went to the Hamptons, there was this narrative that it’s more special than any other place. Wretched shit happens there, too.

I feel my capacity for a real emotional reaction to something I encounter through my phone withering.

BM: When I read the last page of the book, it was such a wake-up call. Jules sitting there on her phone on the beach, just doom-scrolling. The waves are hitting her feet. Her dog might be dying but she’s missing it in a catatonic state. As the author of that, who are you hoping this message will reach?

AT: Me. Every generation right now is totally fucked by their phones. It’s old people with fake news, 30-year-olds with this grasp for relevancy on social media, iPad babies who are—from a biological point of view, their attention spans are just cooked. I feel my capacity for a real emotional reaction to something I encounter through my phone withering. It’s easier to dissociate. It’s easier to hit the button and feel something good for a second than it is to sit and look at nothing and just have your thoughts. I don’t even remember what I used to do before I had everything that I have on my phone right now. It breaks my brain to think about how we’re so dependent on getting something real from the internet when we can’t.

BM: Where did your fascination with crazy moms come from?

AT: I’m thinking a lot about gender and sibling dynamics and family all the time, but especially right now in my life, and there’s this thing that happens with sisters where the older sibling is supposed to show the younger sibling, “This is how you do this.” I think for Jules and Poppy, they want to be mothered. They want to feel safe, they want to be able to look to their family as a site of safety, and they can’t. So they’re in this cycle with each other, and with their mom, of who’s in and who’s out. It’s the same thing as the internet. It’s that same compulsion of, can I feel a moment of goodness here, even though I’m engaging in a really destructive behavior to get it, or I’m sublimating myself to get it? I think it’s all connected for them, which I hope is clear.

BM: I wanted to ask about the darkness of the world that they live in. In some ways, it feels like the New York of Girls, where Hannah’s internal darkness bleeds out onto the city. What do you think about that comparison?

AT: I’ve lived here for a decade. When I’m doing really well, it feels like a gift to live here. I’m going on walks every day, and it feels like I have a personal relationship with New York. When I’m doing really badly in my personal life, it feels like everything is this huge conspiracy that’s out to ruin my every fucking moment. I can’t leave the house. And when I do leave the house, I’m stepping in shit or getting yelled at for bumping into something. You see what you want to see in a place that’s so big and constantly changing. My relationship to this place changes based on my relationship with myself. I think Girls does show you that. There are scenes where she’s running with her boyfriend and she’s like, “I hate this, but I can do it.” And then, there are scenes where she’s holed up in her apartment, physically torturing herself with sticking Q-tips in her ear, getting splinters on her floor.

BM: How does Jewish guilt fit into Jules’ character?

AT: I didn’t grow up very religious at all, but I feel so culturally Jewish. There’s this great scene in The Curse, the Nathan Fielder show that premiered in 2023, where his wife is doing the Shabbat ritual, and she’s overdoing it. Then it’s his turn to say the blessing, and he compulsively says “Baruch atah Adonai…” That encapsulated so much of what I was trying to do with religion in this book. Jewishness to me has never been about belief or an intensity of doctrine or dogma or trying to convince other people of something. But so much of religion is designed to control people and repress people.

Jewishness to me has never been about belief or an intensity of doctrine or dogma or trying to convince other people of something.

I think when you’re like Jules and Poppy, and you’re kind of a bad Jew and you’re not really invested in a religious life, you’re wondering, “What am I missing? Am I not doing enough? Am I disappointing my parents? Am I disappointing my community?” I wanted to look at radicalism and the compulsion to have a belief system when everything about the world to Jules and Poppy says there’s no reason to have a belief system. Everything’s horrible, everything’s random. And yet, the way that Fielder’s character can just mutter these 15 words in a language that he doesn’t even speak, that’s a weird form of control too.

Illustrations by Sasha Fletcher

FURTHER READING

|