David Hill on whether the middle class writer is a myth.

This is part of a new series on The Middle Class Writer from Dirt and Literary Hub—talking frankly about the role of money in the life of a writer in 2024. We'll be publishing on both websites throughout the week.

“It’s money I want, or rather the things money will buy; and I can never possibly have too much.… More money means more life to me. The habit of spending money, ah God! I shall always be its victim. If cash comes with fame, come fame; if cash comes without fame, then come cash.”

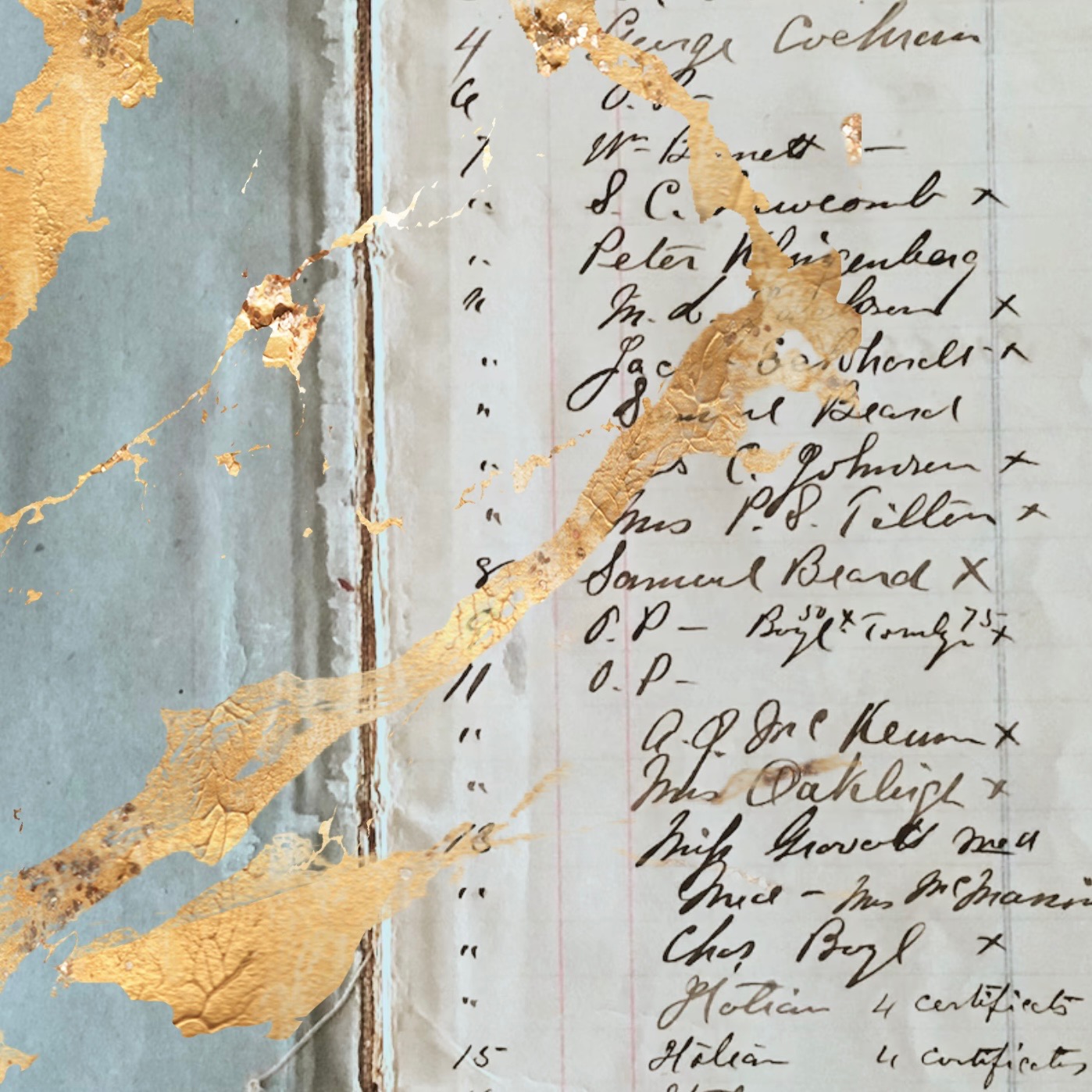

This passage is from a letter written by Jack London, most famous for Call of the Wild, in a response to a letter from one of his fans in 1899, a postal employee from California. London spent his life writing everything from novels to short stories to reported newspaper features: a committed freelancer. He also frequently wrote about workers, their lives, their struggle as a class, and the systems that exploited them. Despite being enough of a success to have fans writing him letters from post offices, the fact is he never earned much money himself. In fact, he actually tried to get on as a postal worker at one point in his freelancing career. If he had been hired, he would have joined William Faulkner, Charles Bukowski, and Richard Wright as postal workers who became successful writers.

The post office makes sense as a pit stop for aspiring writers and lunchpail freelancers. At least at one point in history the work came with a lot of down time, so you could write on the clock. More importantly, however, the job came with a fair wage and decent benefits. It’s tough to do your best work when you’re constantly worried about money. It’s even tougher when, like London, you are the victim of the habit of spending it.

I started writing around 2011, not long after my dad died of cancer. I had just had my first kid. I was living in a hotel in Selma, Alabama, trying to help some autoworkers organize a union with the UAW and found out my wife was pregnant back in New York with our second child. I had been working as a union organizer for more than a decade at that point. I had dropped out of college in 1999 to go on the road with the clothing workers union stirring up shit everywhere from Gun Barrel, Texas to Gun Hill Road in the Bronx. I did that work pretty much non-stop, living out of a suitcase about 200 or more days a year.

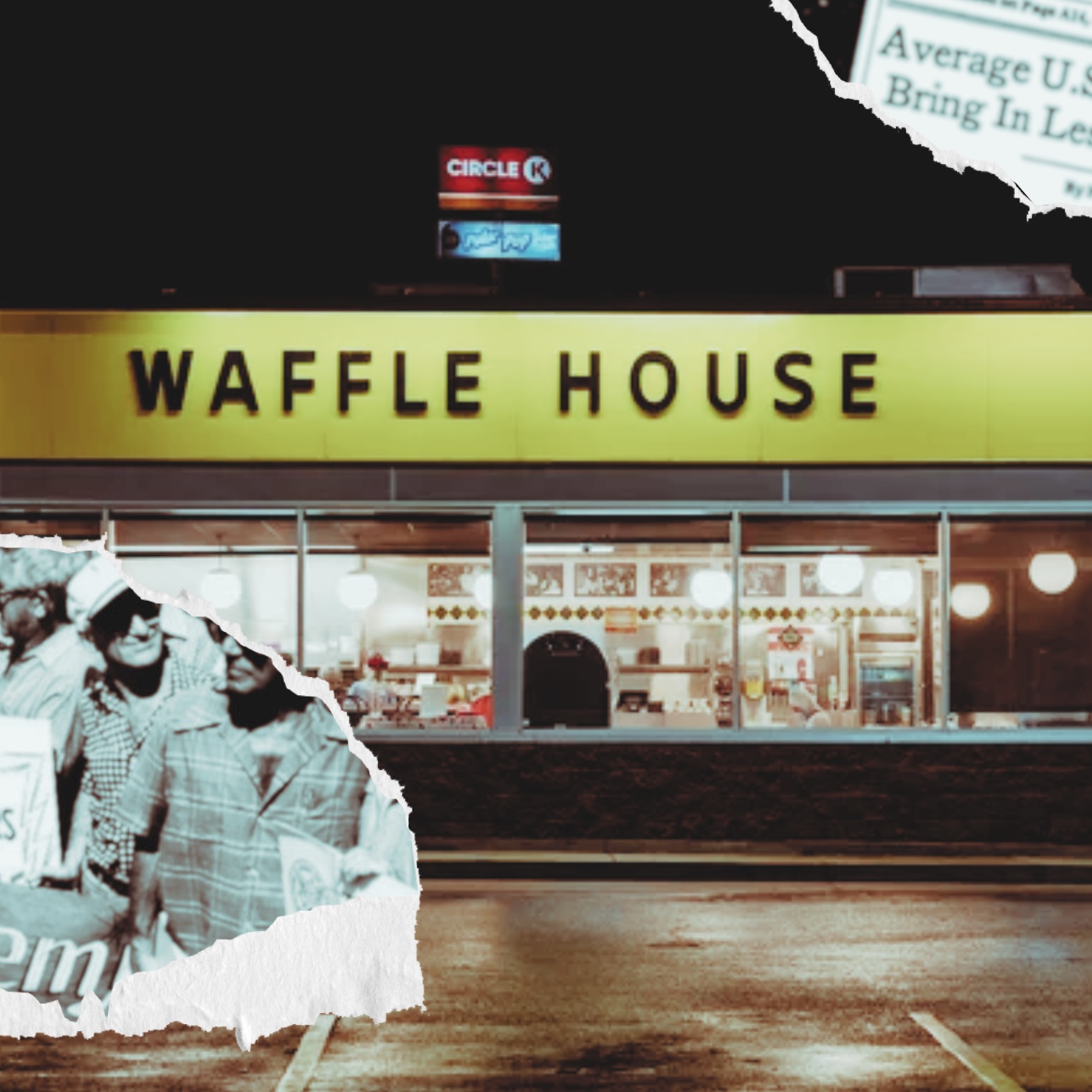

Sometimes to decompress after a difficult day of driving around the sticks and visiting with autoworkers in their homes, I would sit up late at night in the Waffle House near my hotel and write.

By my early thirties, I had grown weary of life on the road, and life as an organizer. It was an exciting life, but also stressful; a life of constant conflict. Sometimes to decompress after a difficult day of driving around the sticks and visiting with autoworkers in their homes, I would sit up late at night in the Waffle House near my hotel and write. Once I knew another kid was on the way, I started thinking writing could be a way out. As a kid I always wanted to be a writer, though it never felt like something I could realistically do. Writers were important people, I reckoned. They went to fancy schools and got MFAs. They interned or spent a year abroad or some other such alien nonsense. They all hung out with each other at oaky taverns or in collegiate libraries with those green and brass lamps. I didn’t know any writers. It was all just a fantasy.

|  | Apr 15, 2024 |

|

|  | Apr 16, 2024 |

|

|  | Apr 17, 2024 |

|

|  | Apr 18, 2024 |

|

|  | Apr 19, 2024 |

|

|  | Apr 20, 2024 |

|